There’s a renewed debate over here recently about what to do with nuclear waste from power stations, research facilities and medical centres. Originally, Germany was supposed to have found a suitable site for a nuclear waste repository by 2031. However, according to a recent government study, the search will be delayed by decades. At least. For the time being, high-level waste from decommissioned nuclear power plants is still stored in interim facilities, mostly on the sites of these plants – whose licences will expire long before proposed repositories are ready.

In addition to the obvious, and urgent, question of how we can safely store our nuclear waste in the long run, from an archaeological perspective the question of such a repository becomes particularly interesting due to its necessarily incredible longevity – and thus the challenge to communicate its potentially lethal contents to our descendants. Low and intermediate level waste has lost most of its radiation hazard after about 500 years; after about 30,000 years, it has a radiotoxicity similar to that of natural granite. High-level waste, on the other hand, still emits about five times as much radiation as natural uranium ore after 1,000 years, and its radioactivity does not fall to the level of natural uranium until 200,000 years have elapsed. Plutonium-239, for example, which along with uranium-235 and uranium-233 is one of the three main isotopes used as fuel in our nuclear reactors, has a half-life of 24,000 years. This means that after this time, only half of the original nuclei will have decayed. Finally, uranium-233 has a half-life of a good 160,000 years (while uranium-235 has only decayed half of its active radionuclides after an incredible 700 million years).

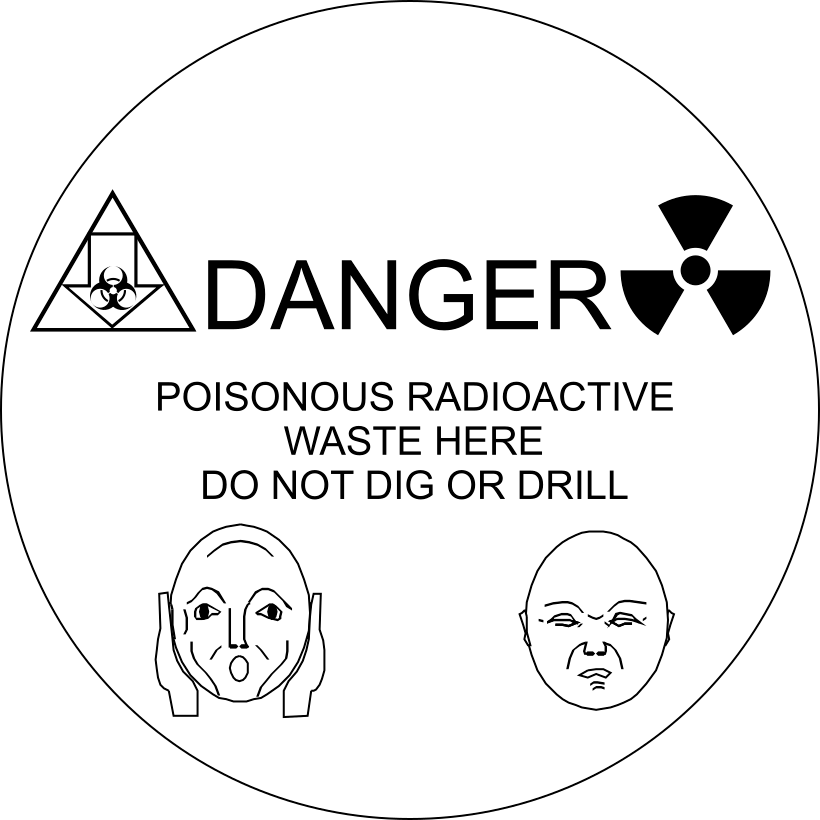

Because of this long half-life of radioactive materials, German lawmakers require their “safe storage for 1 million years”. Yet communicating a warning of its potential danger over such long periods poses somewhat of a challenge. How can we make sure that this message will be understood, that the hazard posed by materials stored in such repositories will still be recognized in, let’s say 1,000 years. Or in 5,000 years, in 10,000 years? Relying solely on written messages does not seem very promising, given how dynamic and changeable language is, even in much shorter periods of time. Looking back from today to the same number of years in history, it is easy to see how difficult it is for us to make sense of some of the messages left by people 1,000, 5,000 and 10,000 years ago. The fundamental question is: would it be enough to simply label such disposal sites in order to communicate their potentially life-threatening contents? If we’re honest, we can well imagine a first reflex that would be triggered by a “Don’t Dig Here!” sign … and it probably won’t be to just leave everything as it is.

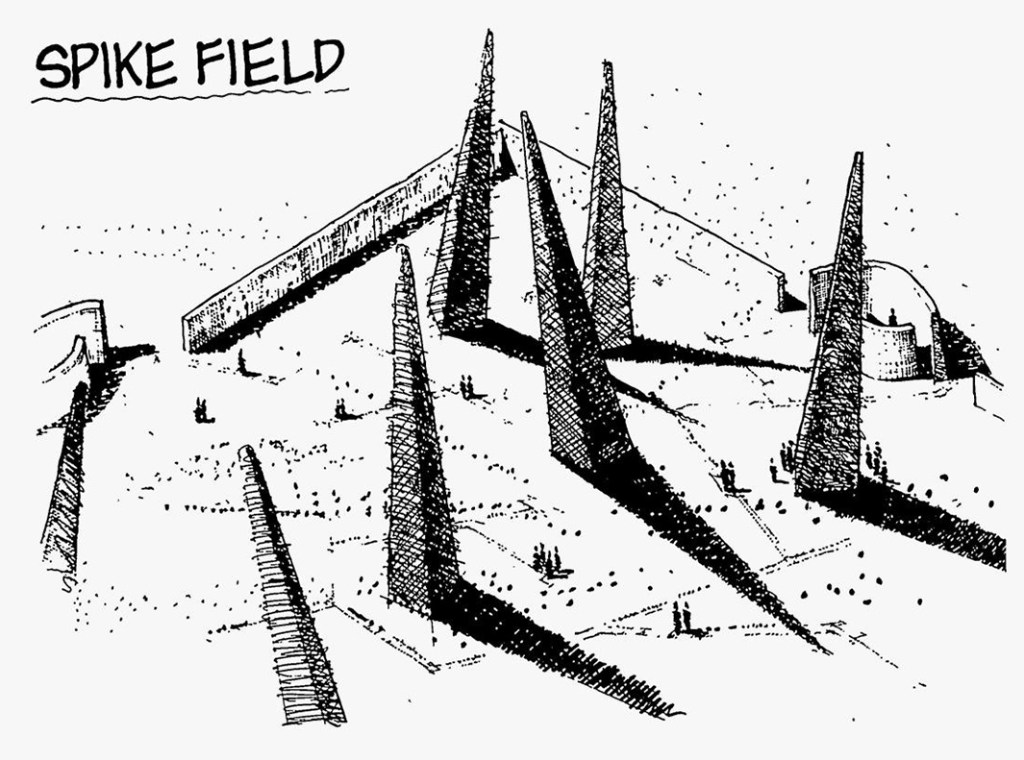

This dilemma is not new, obviously, but has been discussed for as long as the question of how to store radioactive waste safely, and has even spawned its own (albeit rather narrow) academic field, “Nuclear Semiotics”. First established in 1981 by the Human Interference Task Force, an interdisciplinary research group convened by the US Department of Energy, this sub-discipline aims to develop communication measures to effectively deter future humans from intentionally or unintentionally disturbing our radioactive waste repositories. One idea discussed in this context is to clearly mark such places with so-called dangerous architecture, huge thorny sculptures, deterrent monuments that make it clear at first glance that it would be better to stop and turn around. That nothing good awaits you here. But quite apart from the fact that any marker is bound to draw attention to the marked place, how can knowledge of the contents of these repositories be preserved in the long term when these markers have long since crumbled and disintegrated? When any possible symbol we could think of and come up with has lost or changed the meaning we assigned to it – or is interpreted in a way we didn’t intend (I mean … do skull-and-crossbones mean “Poison, keep away!” or “Pirate Treasure, dig here!”?).

Interdisciplinarity was indeed taken seriously in these efforts and thus not only scientists were consulted, but also other experts such as science fiction writers – who, arguably, are predestined to deal with questions of the future by their profession already. Among those, Stanisław Lem for instance proposed a biological coding of such warnings: “Information Plants” that grow only in the vicinity of repositories and provide information about their nature and danger (which raises the legitimate question of who would be able to guess and decipher this in 10,000 years’ time). His colleague Gregory Benford, on the other hand, looked at the technical, environmental and political challenges of nuclear waste disposal, from geological storage in salt flats, the submersion in deep-sea subduction zones, to launching the waste directly into the sun.

Other considerations centered around a long-term transmission of this nuclear legacy’s dangers through enduring narratives. One suggestions was to create a sort of cult, an “Atomic Priesthood”, which would preserve and pass on this vital knowledge over long periods of time under the guise of religious tradition (although Walter M. Miller Jr.’s wonderful 1959 collection of post-apocalyptic science fiction stories, “A Cancticle for Leibovitz”, illustrates that misunderstandings are inevitable when dealing with such long periods of time and expected cultural change … even today’s archaeologists could tell you a thing or two about this). Another idea, much in the vein of Lem had proposed, was the breeding of special cats that would begin to glow in the presence or proximity of radiant material.

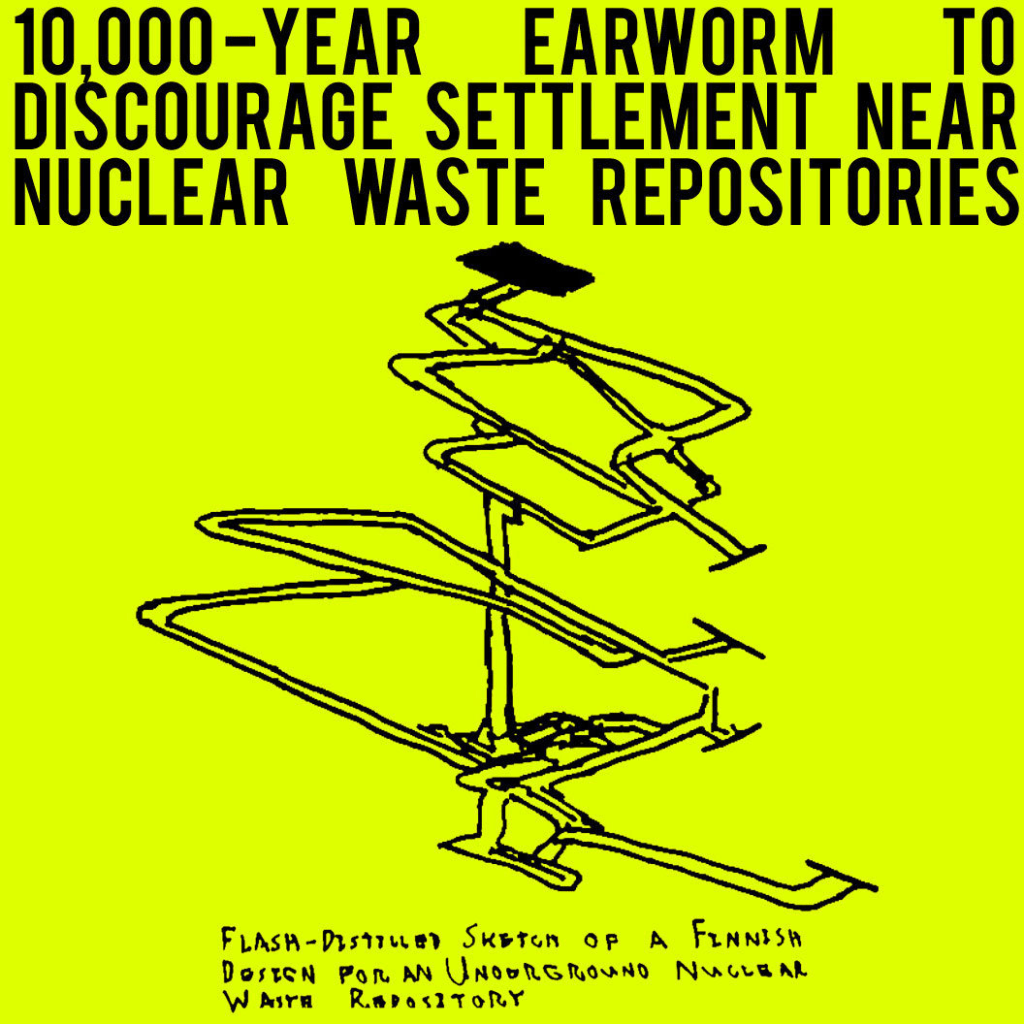

All that remained was to establish a meaning for these “Ray Cats” in the collective memory as an indicator of danger. Like a catchy song – one that would stick for generations. Earworm potential for the next 10,000 years, so to speak; click at your own risk (you have been warned): “Don’t change colour, kitty. Keep your colour, kitty…”

But perhaps marking is not necessarily the most effective approach. Where there is no marking, there is no temptation. At the Olkiluoto repository in Finland, for example, the focus is more on short-term control … and long-term oblivion. A forest is to be created there.