Much has been said and written about the fourth Indiana Jones film – you know, the one infamously featuring, no – not aliens, but “interdimensional beings”. Go figure. Anyway, “Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” still had what is needed to take an ageing Indy – and us – on yet another adventure, tracking down yet another mysterious, long-lost artefact, the eponymous crystal skull, and a secret hidden deep in a long-forgotten ancient city: old Akakor, guarded by the grumpy Ugha people somewhere in the dense jungles of South America.

Make of this plot and its MacGuffin what you will, love it or hate it – but did you know that there is a real story behind the Ugha tribe and their lost city of Akator? And that it makes for just as good a film? Well, admittedly, “real story” might be a bit of a stretch in this case, as we shall see. So let’s stick with “story” – but a story that took place in the real world, involving real people, invented identities and imagined places. And, sadly, some really dark twists. If you thought “Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull” had a cheesy script from popculture’s bargain table, prepare to find the real-life backstory even more outlandish.

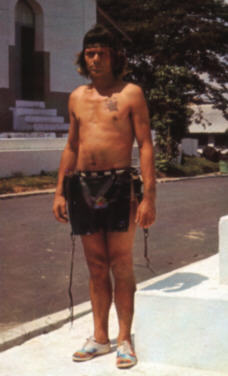

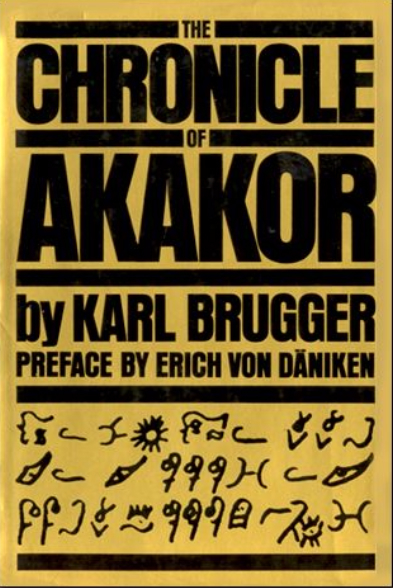

This story begins with the unexpected appearance of a mysterious indigenous tribesman who all of a sudden emerged from the rainforest somewhere in Brazil one summer day in 1972. Introducing himself as Tatunca Nara (which allegedly translates as “Big Water Snake”), he claimed to be an emissary of the Ugha Mongulala (yes, I know: sic!) tribe – whose chief, too, he apparently was. The fact that this “white Indian” spoke little Portuguese but surprisingly fluent German was … remarkable, to say the least (and, spoiler, will play a key role in this story later). Even more remarkable was the tale he was telling anyone who would listen. And German journalist Karl Brugger was one of those who listened with fascination to what this mysterious “Indian” had to say. Apparently, he believed enough of it (or rather, believed in its narrative potential) to write it all down and publish this “Chronicle of Akakor” in 1976 (English edition: Delacorte Press, 1977). – Ah, yes: Akakor. That ancient jewel, that forgotten city hidden deep in the jungle somewhere between Brazil, Bolivia and Peru. Akakor. That underground metropolis which, according to Tatunca’s account, has it all: lost pyramids, occult wisdom, and “divine” ancient alien technology.

Brugger’s book sold, and it fit in well with the zeitgeist of the 1970s. With his bestsellers about ancient civilisations allegedly influenced by extraterrestrials, Erich von Däniken had already prepared the ground for a flourishing esoteric book market, so it is only logical that he contributed a foreword to an English edition of the Akakor Chronicles. Tatunca Nara had touched a nerve. And he could go one better. In the spirit of von Däniken, he reported that the ancestors of the Ugha Mongulala, six-fingered aliens from planet Schwerte, had once come from the stars. But that wasn’t the end of Ugha history: When 2,000 Nazi soldiers made it to Brazil during the Second World War, they joined forces with the Indians. Yes, it is their (white, of course) descendants who live to this day in the underground cities deep in the jungle, the rightful heirs to all the ancient alien super-technology. Which, of course, still exists – and still works. It goes without saying that someone with the reputation of von Däniken couldn’t resist such an opportunity. But the proposed expedition to Akakor failed in chaos. It shouldn’t, however, remain the only one. Tatunca turned his story into a business model and made a career as expedition guide, promising tours to the mythical places of his ancestors – even though every single one of these excursions (Jacques Cousteau was among his clients in 1983) ends in failure and with all sorts of excuses. But after some of his clients disappear under unclear circumstances, and at least one of whom is found dead, questions are raised.

In 1980, an American, John Reed, made contact with the incredible storyteller and followed him into the jungle to learn more about the mysterious ancient kingdom of Akakor. But Reed never returned. Nor did Herbert Wanner from Switzerland, who disappeared in 1983 after staying with Tatunca Nara. His skeleton was discovered by locals a year later, the skull bearing a bullet hole. This in turn prompted Swiss authorities to open an investigation. An investigation that included Tatunca Nara. And when German-Swedish yoga teacher Christine Heuser disappeared in 1987 after visiting the notorious chief, the German Federal Criminal Police Office joined this investigation.

Tatunca Nara has spun a truly colourful tale of Akakor and the Ugha with their mighty ancient empire – not just one lost city, no, but several! Including the obligatory treasure, of course. But if you think this sounds like a pulp novel, you might be onto something. While Brugger (who too died in unexplained circumstances, shot on the street in Rio de Janeiro by an unknown assailant on New Year’s Eve 1984) was somehow convinced of the whole Akakor story (at least convinced enough to find a publisher), it had one major flaw: there was only one source for this fantastic chronicle – Tatunca Nara. Tatunca Nara alone. And when a story sounds too good to be true, it usually is. In the end, it was all down to the efforts of German confectioner-turned-adventurer and activist Rüdiger Nehberg, who in 1990 decided to dig deeper. Together with filmmaker Wolfgang Brög, he persuaded Tatunca to take them on an expedition deep into the jungle. In the course of this journey, they confronted him with the criminal investigation and their own research, and finally exposed the hoax: the self-proclaimed chief Tatunca Nara was: Hans Günther Hauck, a German citizen. Born near the city of Coburg, he had been disappeared in the 1960s (apparently due to financial difficulties), just as unexpectedly as he emerged from the jungle years later, leaving behind wife and children in Germany. The fugitive, not paying alimentory at home, was tracked down by local police in Venezuela, arrested and sent back to Germany, but two years later he flees to South America again. This time to Brazil. And this time he remains missing – until that mysterious tribesman, who emerged from the jungle one summer day in 1972, is finally unmasked.

But the whole Akakor story is still out there. Not just as an echo in the plot of the penultimate Indiana Jones film. Despite having been debunked long ago, Tatunca’s Akakor story is an oft-cited trope that fuels pseudo-archaeological narratives about ancient civilisations to this day, robbing ancient and indigenous cultures of their achievements and history. And this, to say the least, is not really a good thing.