Manufactured between around 3,300 and 3,000 BC, the Arslantepe arsenic-copper swords, famous as the world’s oldest (yet) known such weapons, are evidence of the high level of metalworking in eastern Anatolia at the very beginning of the Bronze Age. But an initial fascination with shiny stones that are soft enough to be hammered into shape, or that behave in strange ways when thrown into a fire, goes back a good deal further. Copper ores and, for the record, other metals have been turned into weapons, tools, and jewellery for much longer. But for how long exactly? And when did a fascination with experimentation turn into metallurgy? These questions are once again becoming increasingly interesting – and not just to archaeologists – thanks to some recently published new analyses from another site in Türkiye.

Photo: Diyarbakır Müze Müdürlüğü, Anadolu Ajansı

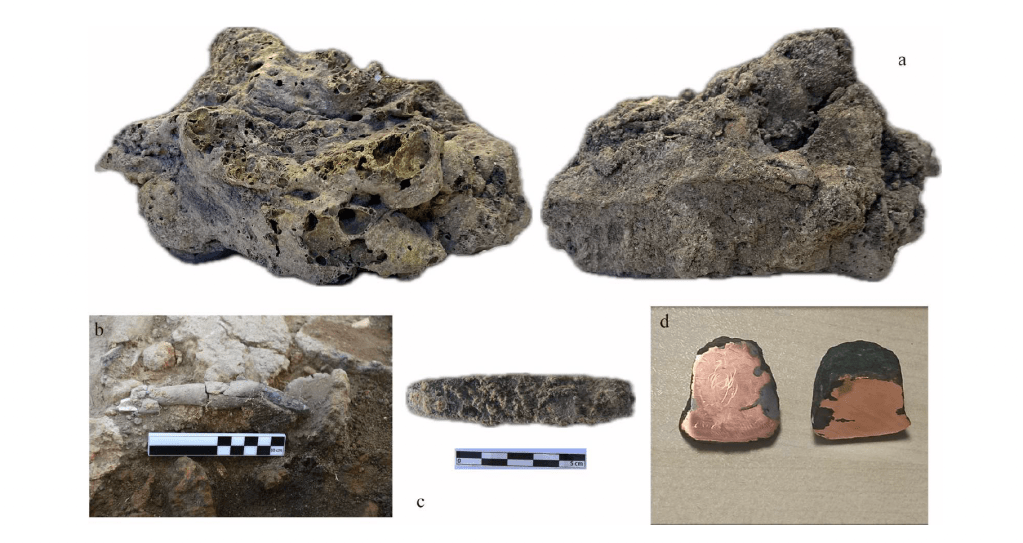

Excavations conducted by colleagues from Kocaeli Üniversitesi since 2018 at Gre Fılla, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic (PPNB) site in Diyarbakır in the Upper Tigris region, have revealed vitrified material and copper artifacts suggesting that Anatolian hunters may have experimented with pyrometallurgy earlier than thought in the region. Spectroscopic and chemical analyses, in particular of the apparently molten material (including copper droplets) as well as larger copper objects, indicate that they have been subjected to very high temperatures in excess of 1,000 °C – accidentally or intentionally? The greatest challenge in these early metallurgical experiments, indeed in any such metallurgy, would be the mastery of fire control. Of the extreme heat required for smelting (i.e. reducing the ore from the waste rock, not to be confused with melting) – which is rather different form cold-working copper, but thus an even more fascinating shifting transition.

Minerals like malachite or native metals such as copper were undoubtedly picked up and collected early in the wanderings of our ancestors, if only for their vivid colour (with earliest hints at gold use dating as far as back as the Paleolithic). And as much as gold, silver, tin and even meteoric iron were tested for their material suitability, pieces of pure copper, too, were cold forged and shaped, sometimes partially heated, hammered into sheets and folded into beads or tools. In Anatolian Neolithic sites like Çayönü Tepesi in the Upper Tigris region (where copper artifacts have been found in remarkably large numbers, whereas they are rare in contemporary settlements in the region), such cold metallurgy can be traced back more than 10,000 years, and still as far back as 8,700 years ago on the Syrian bank of the Euphrates, for example at Tell Halula; more frequent copper use finally spreading in the region during the Halaf culture in the 6th millennium BC.

Evidence for smelting in the region comes from Yumuktepe in Mersin around 5,000 BC. The first clearly documented cast metal objects there date from this time, as does evidence of smelting with the contemporaneous slags from Değirmentepe north-east of Malatya (even older slags, 8,500-year-old “high-temperature debris” reported from Çatalhöyük, long thought to be further probable evidence for early pyrometallurgy, were finally identified as accidental products of copper minerals in burials reduced in post-depositional fires).

of copper object (d).

Figure after: Muşkara et al., J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 62, 2025

Yet these new findings from Gre Fılla in Diyarbakır are more than just a few slags. Although actual and deliberate smelting has yet to be proven, there is evidence of vitrified materials as well as copper objects and tools, apparently coming from contexts dating to the early Neolithic period, around 9,000 years ago, according to the study’s authors. More intriguingly, the isotope analyses also showed that at least some of the copper did not come from nearby deposits, but from further afield, from the Black Sea region – perhaps suggesting the existence of long-distance copper trade networks as early as the Neolithic.

There’s an Ea-Nasir joke in there, but I’ll keep it to myself.

Original study: Ü. Muşkara et al., Early copper production by the last hunter-gatherers, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 62, 2025: 105051. 🔐💵