Warning: This article contains rather gruesome descriptions of ancient torture and execution practices, as well as images of human remains.

It’s Good Friday, the day Christians commemorate the crucifixion of Jesus, which according to Christian tradition took place in 1st century AD Judea under Roman rule. You’ve probably heard the story, or maybe even seen that really grim film. And while there are numerous written accounts of crucifixion as a means of punishment and execution in ancient Rome, actual archaeological evidence of the practice from Roman times remains scarce. So, for a bit of Easter archaeology, let’s look at the few examples we do know about.

As a method of capital punishment, crucifixion predates the Roman period and goes back to Phoenician, Assyrian and Persian times. In ancient Rome, it was inflicted on slaves or as a political punishment, for example for insurrectionists – but not usually on Roman citizens. The crucifixion of Jesus lies at the heart of Christianity, and the cross has become its pre-eminent religious symbol. His death is arguably the most prominent example of crucifixion in history. The written historical record, however, including Seneca, Plutarch, Josephus, Appian and many others, not only gives us some insight into the often gruesome details of this practice, but also suggests that it was not a rare punishment, particularly in times of political turmoil, as Josephus notes (Wars of the Jews, V, 11.1):

“… while they caught every day five hundred Jews (…) nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another to the crosses, by way of jest. When their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses; and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

Considering these numbers alone (and that’s just one example of a much richer variety of such reporting), the archaeological record of crucifixion from this period seems surprisingly rare in contrast. Or maybe not so surprisingly. Our popular image of crucifixions is largely based on those dramatic depictions, from art history to Hollywood, in which nails are driven through the hands and feet of the condemned. However, the lack of associated finds of nail-pierced bones may simply point to other forms of actual fixation of delinquents to the cross.

Given that the entire weight of the body on the cross had to be supported by these nails, it seems very unlikely that they were attached through the hands. Artists throughout history have tried to answer this by coming up with other, more practical and indeed possible means of fixation, such as condemned criminals being tied to the cross rather than nailed. And more recent historic (but not less cruel) records do, at least sometimes, seem to confirm these options.

Sometimes a footrest can be seen in depictions, perhaps for this very reason, to take the weight off the crucified person’s wrists – but it is not described in the ancient sources. They do, however, occasionally mention a small seat attached to the front of the cross, which may have served a similar purpose. Another possibility, which would not necessarily require tying, is that nails were inserted through the soft tissue just above the wrist, right into the gap between the two bones of the forearm. While depictions, probably in reference to accounts of his wounds (John 20:25), show nails driven through Jesus’ hands, the word used in the Greek original, χείρ, actually refers to the whole arm below the elbow.

Moreover, given that this punishment was reserved for insurgents (considered criminals by the Roman Empire) and slaves, it is likely that their bodies were not regularly buried according to established ritual and tradition (apart from high-profile exceptions where advocates may have been able to negotiate proper burial), but may have been treated in some other way that left no visible trace in the archaeological record, particularly once the nails (if used at all) had been removed when offenders were taken from the cross. Without nails observation of evidence for crucifixion becomes less likely, if not impossible. This may explain, at least in part, why we have so little tangible evidence of Roman crucifixions and their victims, despite the fact that they seem to have been quite common, at least according to written sources. Yet little does not mean nothing, and there are indeed a few rare archaeological finds that point to ancient crucifixions. Four so far, to be precise – some more and some, well, less clear.

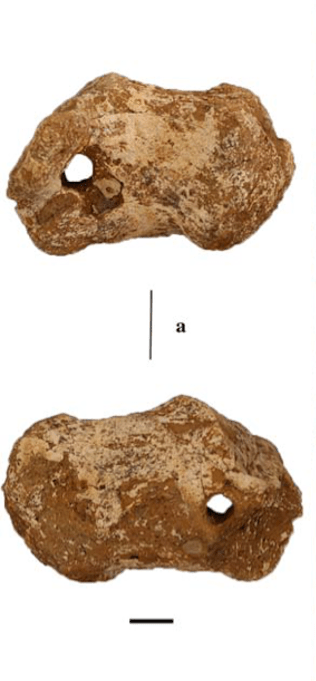

Figure from: E. Gualdi-Russo et al., Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11(4), 2019 (via Springer Nature)

One such example comes from an isolated 1st century AD Roman burial discovered in 2007 in Gavello in northern Italy. This isolation and the fact that the man, who died in his thirties, was buried without any grave goods, already emphasise the peculiarity of the find. A round hole in the man’s right heel bone, running from the inside to the outside of the foot, appears to have been inflicted around the time of his death. And although the skeleton was not perfectly preserved, the excavators ruled out an accidental origin for the hole, interpreting the lesion as a puncture wound, almost certainly caused by a single nail that pierced both heels.

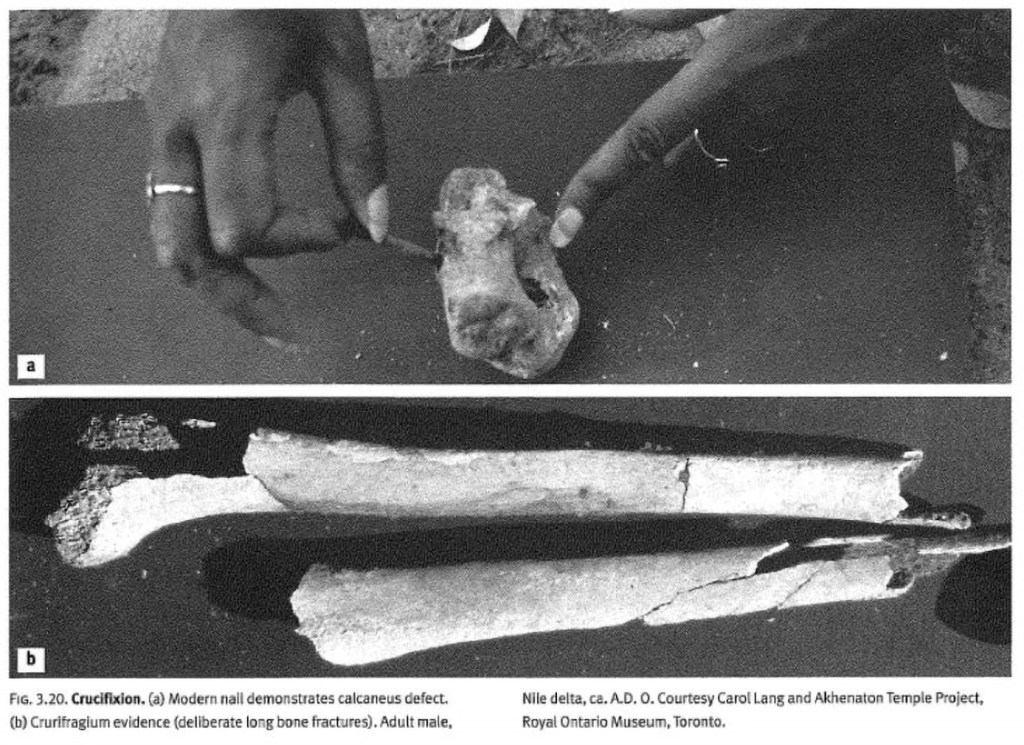

Figure from: A. C. Aufderheide and C. Rodriguez-Martin, Crucifixion, in: The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Paleopathology (Cambridge 1998), original credit to Carol Lang and Akhenaton Temple Project, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto.

Another case was made with burial finds from Mendes Harbor in Egypt, dating between the 1st centuries BC to AD. Here, too, a heel bone was showing a round hole through both sides. In addition, two shinbones were found with fractures which have been interpreted as evidence of crurifragium, the practice of breaking the legs of the crucified to hasten death. However, these interpretations have been challenged by other colleagues, as crurifragium is not the only possible cause of the broken long bones, and it has been pointed out that the damage could even have occurred much more recently, judging by the lighter colour of the fracture edges seen in photographs. The holes in the heel bone, on the other hand, also seem inconsistent, appearing to be of different sizes and not at the same height, and it was concluded that root activity was certainly a more probable explanation for the hole.

Photo: A. Williams, via Albion Archaeology

In 2017, a heel bone pierced by an iron nail, dating to the 2nd to 4th century AD was reported from England. There, at one of the five cemeteries found around a newly discovered settlement at Fenstanton, between (then Roman occupied) Cambridge and Godmanchester, a man aged between 25 and 35 at the time of his death had been buried with his arms across his chest – and, well, that nail. Right through his right heel. After careful examination, it was concluded that this rather unsubtle finding was most likely the result of: crucifixion.

Photo: D. Winterburn, CC BY-ND 2.0

Perhaps the most famous of these examples is that of a man who lived in the 1st century AD and was known as Jehohanan the son of Hagkol (or Ha-galgula, the meaning of the original hgqwl is uncertain), according to the inscription on the stone box containing his bones, discovered in 1968 at Giv’at ha-Mivtar in East Jerusalem. Apparently he died on the cross, too: at least that’s what his right heel bone, pierced by an 11.5 cm iron nail, suggests. Even traces of the wood it was attached to originally are persevered. An initial anthropological analysis in 1970 concluded that Jehohanan was crucified with his arms outstretched and his forearms nailed, possibly on a two-beam cross. However, a later reassessment suggested that a horizontal beam was attached to vertical stakes and that, with his arms bound, he died of asphyxiation.

But what all these finds have in common is that we only know about them because these crucified individuals have been properly buried. Which probably wasn’t the norm. On the contrary it was likely rather unusual for a crucifixion victim to be reclaimed, brought back and buried, as it has been argued that part of the punishment of crucifixion was that the bodies were not taken down, but rather left to be consumed by birds of prey or to decay naturally on their crosses. This makes these four, or rather three cases pretty special – and it may explain why we don’t have more evidence for ancient Roman crucifixion.

Closing remarks: In 337 CE, Emperor Constantine abolished crucifixion in the Roman Empire.