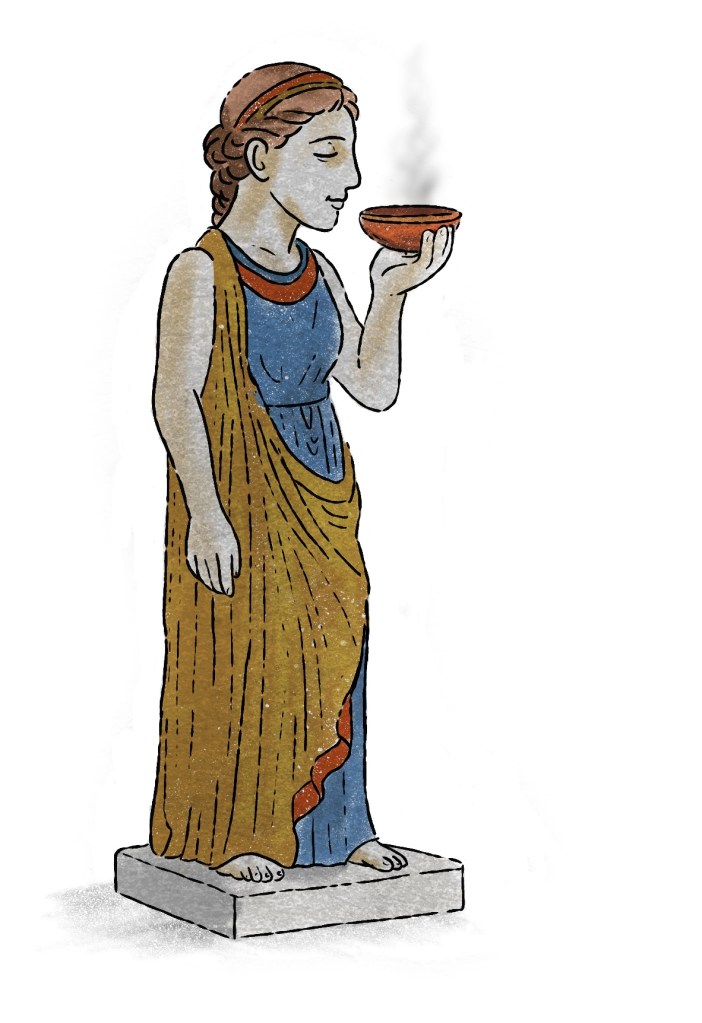

It is now common knowledge that our image of immaculate white marble statues does not correspond to an ancient tradition, but rather to a beauty ideal originating in Renaissance art and that has been perpetuated developed in art history since at least the 18th century (looking at you, Winckelmann), still propagated in the 20th century as the aesthetic superiority of formal austerity. However, a new study suggests that these sculptures were not only painted in vibrant colours in the past (which maybe even seem a little kitschy today), but also apparently exuded their own fragrance.

Photo: Marsyas, CC-BY-SA-2.5

In a recent paper published in Oxford Journal of Archaeology, Cecilie Brøns, a curator at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen, describes how references to fragrant statues captured her attention while she was reading through ancient texts. Intrigued, she began a systematic search for further references and discovered descriptions of scents, ointments, and flavoured oils used to “decorate” cult images in the works of Cicero, Callimachus, Vitruvius, Pliny the Elder, and Pausanias, among many other ancient writers.

Callimachus, in his 3rd century BCE poems honouring Berenice II, wife and co-regent of Ptolemy III, describes a statue of the queen as “wet with perfume”. And in his “Speeches Against Verres” from 70 BCE, Cicero refers to a sculpture of the goddess Diana (Artemis in Greek mythology, areas of responsibility: hunting, forests, and animals) in Segesta, Sicily, which was rubbed with precious oils and crowned with flowers as it was led out of the city. On the Cycladic island of Delos, where ancient sources even suggest the existence of an entire perfume workshop, temple inscriptions detailing the equipment required for the cult centre prove that statues of Artemis and Hera (goddess of marriage, women, and family) were anointed with beeswax and rose oil. The 2nd-century CE Greek geographer Pausanias also reports in his “Description of Greece” that the famous statue of Zeus in the sanctuary of Olympia was regularly treated with olive oil to protect the ivory from the humid climate.

This practice is actually part of an intricate ancient ritual for adorning images of deities. As well as painting, clothing and jewellery, it involved applying waxes and ointments (ganōsis), impregnating the statues with oil (kosmēsis) and perfuming them. While pigments and paint residues have occasionally been detected on ancient statues, it is naturally more difficult to detect fragrances. Even floral wreaths and garlands, which may have provided an additional scent, are not usually preserved unless they were made of gold or clay, as some finds demonstrate. However, other sources tell us about the common practice of placing flowers in sanctuaries and on images of goddesses and gods, for example during the Roman Floralia festival, which was usually celebrated in April and May.

The intention behind this – and this is what makes the discussion so exciting – was to create a multi-sensory experience of the images of gods. These images were not just stone carvings; they embodied the deities they depicted. To visitors of the ancient temples, these deities appeared to be truly present: entities that could be seen, smelled, and perhaps even touched. The smell of all these goddesses and gods has long since faded, but anyone who, upon entering an old church, has ever been overwhelmed by the heavy scent of incense that has seeped into the woodwork and stone for centuries may recall the effect of fragrances in sacred places. They have the power to anchor the divine in space.

For archaeology, which relies so heavily on the visual, this sensoial turn opens up a new way of bringing us closer to the people of the past and their world. Allowing us to take a deep breath, so to speak.

The original article can be found online here: C. Brøns, The Scent of Ancient Greco-Roman Sculpture, Oxford Journal of Archaeology 44(2), 2025. 🔐💵