“We hope to get through this region in a few days, and are camped here for a while to arrange for the return of the peons, who are anxious to get back, having had enough of it – and I don’t blame them.“

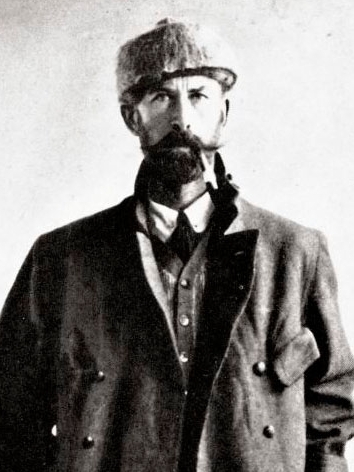

The mosquitoes really annoyed him. In his letter to his wife, written at the end of May 1925 on the Rio Cululene in the middle of the Brazilian rainforest, Percy Harrison Fawcett, an off-duty Royal Artillery officer and cartographer, made this clear. Nevertheless, he was confident that the destination of the journey would make up for all these hardships:

“You need have no fear of any failure.“

The closing words of his letter were hopeful and almost pleading. It was to be his final testimony. Here, at Dead Horse Camp (named after his horse that had died there five years earlier), Lat 110 43′ S – 540 35′ W (or elsewhere, as the journalist David Grann discovered from notes provided by whose family, Fawcett apparently laid a false trail), every trace of the expedition was lost on 29 May 1925. Fawcett, his son Jack, and Jack’s friend Raleigh Rimmel had separated from the hired local porters and continued alone. In the then largely unexplored Mato Grosso region of Brazil, the three Britons disappeared in the eponymous “Thick Bush” and were never seen again. Yet even 100 years later, they and their legacy are astonishingly present: Fawcett’s disappearance while searching for a mythical city hidden in the jungle has long since become an archetype, and the idea of lost civilisations has become firmly embedded in popular culture.

Born in August 1867 and brought up in the pioneering spirit of Victorian tradition, Fawcett is usually placed somewhere between colonialist explorer and tragic hero in today’s and yesterday’s reporting: He came from a parental household of old (albeit impoverished) Yorkshire gentry, melding Royal Geographical Society (his father) and occultism (his mother), but lacked warmth. A military career (Royal Military Academy) and finally, from 1886, service as a lieutenant in the Royal Artillery allowed him to travel quite a bit: Hong Kong, Malta and Ceylon. This left an impression and he took the opportunity to study surveying and cartography with the Royal Geographic Society – just to join, now promoted to lieutenant, a mission for the Secret Intelligence Service as a surveyor in Morocco. Followed by three years of service with the War Office in Cork from 1903 to 1906, which Fawcett completed as a major.

In 1906, he finally travelled to South America for the first time. Once again working as a surveyor, this time for the Royal Geographical Society. The Society had offered to act as a neutral mediator in the border disputes between Bolivia and Brazil, fuelled by the increasing demand for rubber as the automotive industry boomed, in order to map the border region and determine its exact course. By 1924, Fawcett had undertaken a total of seven such surveying expeditions in South America, interrupted only by his voluntary service in Flanders during the First World War, which earned him a Distinguished Service Order and the promotion to lieutenant colonel. A note from the Royal Geographical Society suggests that his expeditions were rarely walks in the park for his companions, as Fawcett always went a little further than most others would consider appropriate or even possible.

During this time, he mapped part of the border with Peru and the upper course of the Beni River in the Andes on behalf of Bolivia. He then travelled further into the heart of the country. It was already in Ceylon that he first felt called to be an explorer, reportedly investigating rumours of hidden treasures and exploring ancient ruins. In South America, it seems that he was following the advice of Rudyard Kipling’s 1898 poem “The Explorer” (which he is said to have carried with him):

“Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges -Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!“

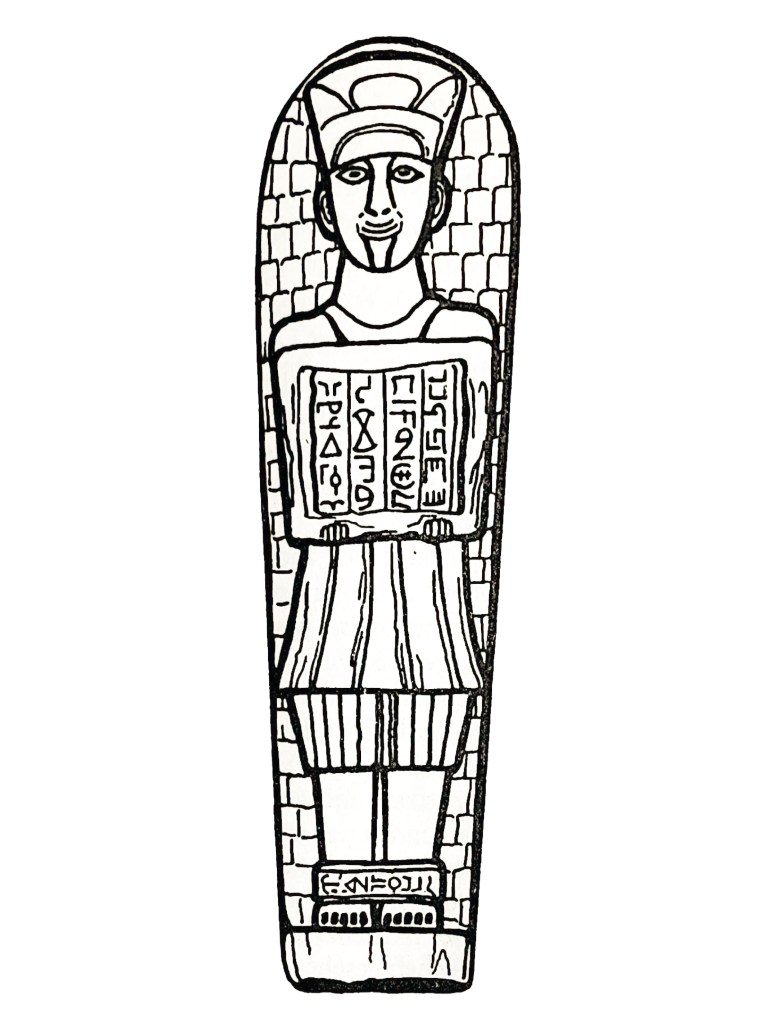

In addition to some cryptozoological observations of giant anacondas, gigantic spiders and double-nosed dogs, which he telegraphed home (to a reserved reception), Fawcett also began to develop his ideas about the “forgotten city”, which he called “Z” and which he believed to be evidence of an unknown advanced civilisation in Mato Grosso. A document in the National Library of Rio de Janeiro, now known as “Manuscrito 512”, likely fuelled his spirit of exploration. It recounts the supposed discovery of an ancient city in Greco-Roman tradition by a group of Portuguese adventurers in the 18th century, a tale which had already captivated Richard Francis Burton, as well as Fawcett. Naturally, it does not mention the mysterious city’s exact location and is so vague in other respects that one can cast serious doubt on its authenticity. However, Fawcett supposedly had another ace up his sleeve: a stone idol whose place of origin a medium confirmed to him was none other than the legendary Atlantis.

The figurine itself seems simple, but the view of the bearded little man with the hat and the hieroglyphically decorated plaque in front of his chest is suspicious enough to make one agree with the British Museum colleagues to whom Fawcett had shown the gem – and who thought the figurine was fake. Needless to say, he could not be satisfied with this. After all, he had received the piece from Henry Rider Haggard (who wanted to have acquired it in Brazil). The same Haggard who had achieved fame as author of exotic, colonialist adventure novels such as stories about the big-game hunter Allan Quatermain, which were very popular in Fawcett’s youth.

Fawcett’s proximity to a more esoteric worldview is already evident from his time in Ceylon, where he met Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, a prominent occultist and key proponent of modern theosophy (his older brother Edward had provided research for her “Secret Doctrine”). In Fawcett’s mind, “Z” was an ancient, ruined site that could undoubtedly compete with the monumental buildings of the Maya and Incas – he was undoubtedly familiar with John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood’s reports from the 1840s of overgrown temples and pyramids in the Mexican, Guatemalan and Honduran jungles, and the (re)discovery of Machu Picchu by Hiram Bingham had occurred just ten years earlier. At a time when interest in the historical monuments of the “New World” had moved on from the gold rush of the conquistadors to scientific curiosity, Fawcett wanted to contribute something too – and even go one step further. He assumed his city ‘Z’ to be 11,000 years old and considered it to be more than just an archaeological mystery; for him, it was a spiritual centre and the legacy of a lost civilisation. It was an outpost of Atlantis and – in theosophical tradition – a place of hidden knowledge from which all of humanity would benefit.

Although he describes the natives benevolently and is interested in their language and customs, he cannot escape the trap of viewing them as anything but equal through the colonialist, Eurocentric lens of his time. The Indians, he states, are docile people who can be easily tamed. Or, where this was not the case, repulsive cannibals. A third group, he considered particularly robust and noble, seemed to be of “civilised origin” and therefore further evidence of the ancient civilisation he was searching for. The Atlantis link leaves little doubt as to where he situates this origin historically. And he justifies this with rumours about supposedly “white Indians”, whom he had heard were repeatedly sighted in the Amazon. In his notes, Fawcett describes these supposed descendants of Atlantis’s fleeing population as superior to the indigenous Amazonian tribes. He is convinced that they alone would be capable of the cultural feats for which the forgotten city of “Z” has come to embody. And even though the natives repeatedly assure him that, if such sites existed in the jungle, their own ancestors would have built them, he finds this rather doubtful.

On the expedition in spring 1925, which would be his last, Fawcett embarked on an archaeological and, above all, an esoteric journey of discovery. Perhaps Fawcett’s disappearance, along with his two companions, lends itself so well to mystification because it offers such a large projection surface – from adventurous daredevilry and the exploratory urge to discover, to the spiritual search for meaning – and because so many expectations, so many possibilities are associated with it. When news suddenly dried up around four months after the expedition began (more than 40 million readers had been following the dispatches from the jungle, for which a consortium of North American newspapers had acquired the rights), uncertainty reigned, but in accordance with Fawcett’s wishes, the Royal Geographical Society continued to wait. By keeping his route secret from potential competitors, Fawcett had not made it easy for potential rescuers. It was only when personal belongings from the expedition were found in the possession of Indians that a rescue expedition was organised in London. Led by George M. Dyott, it set off in 1928. However, the men get into trouble themselves, reporting serious problems with the natives and that they only narrowly escaped death. Fawcett, on the other hand, was less fortunate according to this report: his expedition perished at the hands of hostile Indians in July 1925, they found out. Dyott, however, failed to provide conclusive tangible proof.

Those who had not yet given up on Fawcett could have gained new hope when, in the early 1930s, a Swiss trapper reported meeting a bearded man in the jungle who (far from his last known position, though), allegedly identified himself as Fawcett, apparently a prisoner of the Indians accompanying him. The further search for the mysterious man, however, remained unsuccessful. This was not to be the last search mission, but only a few returned with results (and some did not even manage that). In the years that followed, other pieces of equipment did turn up, including a theodolite proven to have belonged to Fawcett and, later, his signet ring, but there was still no trace of the lieutenant colonel himself, his companions, nor their remains.

These were not made public until 1951 (apart from the description of a shrunken head a few years earlier, which looked or could have looked like Fawcett), when Brazilian anthropologist and Indigenous rights activist Orlando Villas Bôas presented a skeleton that had been given to him by the Kalapalo Indians. Analyses had clearly and unequivocally identified the bones as belonging to the missing British adventurer. However, the consternation did not last long, as further independent studies again unequivocally showed that the bones were not Fawcett’s at all. This was finally confirmed by the Kalapalo people, who had become the focal point for all search teams ever since they last hosted his expedition. In an attempt to restore calm, they passed off the remains of a former chief as Fawcett’s. However, the Kalapalo now repeatedly and vehemently emphasised that they had nothing to do with the group’s disappearance. As early as 1931, long before the discovery of Villas-Bôas, an expedition sent by the Penn Museum documented what the Indians reported about their last encounter with Fawcett – and what, recorded more than five decades later by the ethnologist Ellen Basso, found its way into the tribe’s oral history: According to the Indians, Fawcett and his two companions ignored the warnings of hostile tribes and continued eastwards after resting with the Kalapalo. The smoke from their campfires could be seen for five days, and Kalapalo hunters discovered traces of these camps, but did not see the white men again.

This uncertainty lies at the heart of Fawcett’s ongoing legacy, as it allows to avoid coming to terms with his sudden death. It provides fertile ground for rumours and myths to grow: what if the men had actually reached their destination – the mysterious city of “Z” – and settled there with its inhabitants, the descendants of those Atlantean refugees? Or what if they had started a new life far from civilisation, with Fawcett becoming the chief of a native tribe? Perhaps the men had never intended to return to England and had instead planned to found a theosophical commune in the jungle from the outset? As far-fetched as these scenarios may sound, they have indeed been considered and proposed in the past. Even a supposed son of Jack Fawcett was found and presented to the public: A fair-skinned 17-year-old Indian named Dulipé – whose unusual appearance was quickly revealed to be due to albinism.

Over the years, the speculation surrounding Fawcett became increasingly fantastical, and the search for him became as esoterically charged as his own quest. It was said that he had not only found his lost city, but also enlightenment or even the gateway to another dimension. Fawcett, a border crosser who had no fear of contact with the occult and who was already considered the archetypal “explorer” during his lifetime (which he probably did not mind), became a spiritual icon in popular culture. Media coverage of his expeditions and surveying missions contributed to this, as did a series of public appearances and lectures. One of these, at the Royal Geographical Society in February 1911, made an impression on Arthur Conan Doyle (the creator of Sherlock Holmes, who was also one of Fawcett’s author acquaintances, along with Kipling and Haggard). Doyle’s novel, published the following year, set in a “Lost World” populated by primeval animals on a South American jungle plateau, obviously drew heavily on this exchange. The inspiration appears to have been mutual: in his diary, Fawcett seems to consider such a scenario to be at least conceivable (even if there is disagreement as to whether he was the model for the Professor or Lord Roxton’s character in the novel, or neither):

“Monsters from the dawn of Man’s existence might still roam these heights unchallenged, imprisoned and protected by unscalable cliffs.“

Fawcett’s youngest son Brian compiled these diaries and notes from the explorer’s estate and published them posthumously in the 1950s, along with the draft of a manuscript about his expeditions (the last of which was, of course, reconstructed solely from the letters, field dispatches and journals sent from the jungle). They consolidate the explorer’s biography, but also portray Fawcett as a man fixated on a single goal. There are few descriptions of the country and its people, or more detailed observations of the flora and fauna in the undeveloped Amazon at that time (which would certainly have been of scientific interest, even beyond giant anacondas and spiders). Fawcett’s primary interests were obviously his mapping missions and, later, the search for “Z”; everything else had to be subordinated to these.

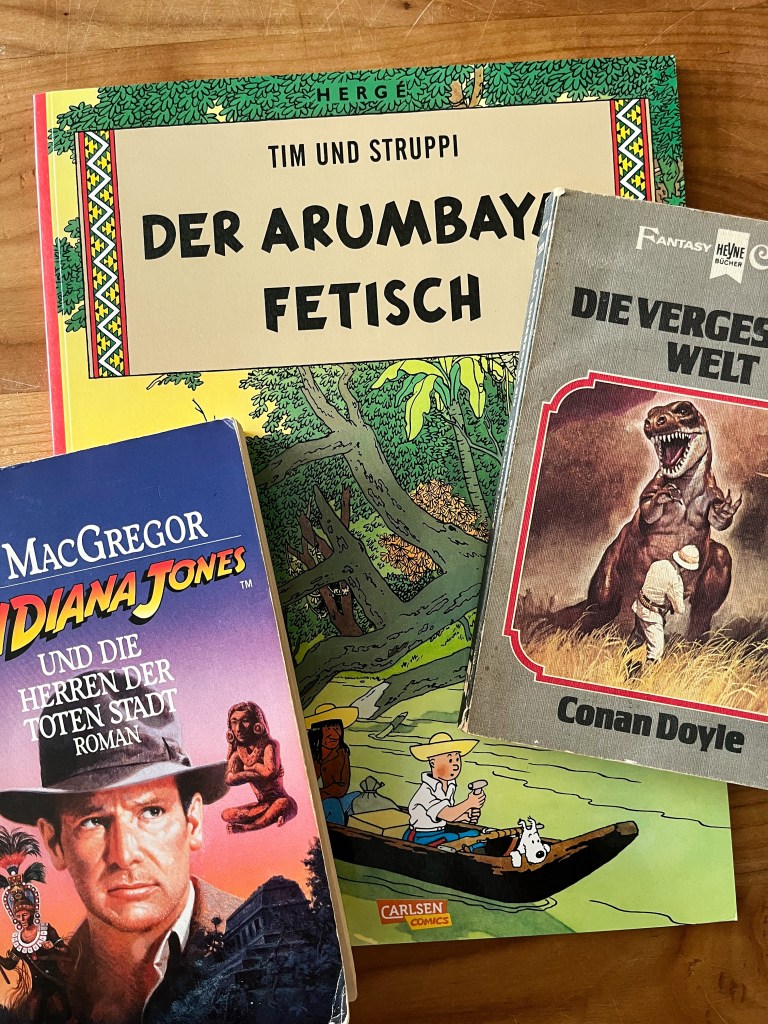

Later examinations of Fawcett’s personality as an explorer usually focus on this very search, somewhere between single-mindedness and obsession, which is inextricably linked to his disappearance. And the story of his lost expedition has received extensive media coverage: Starting with accounts of the earliest rescue expeditions, such as Dyott’s “Manhunting in the Jungle” (1930) and Peter Fleming’s “Brazilian Adventure” (1933) as well as Robert Churchward’s description of the same jungle journey in his “Wilderness of Fools” (1936) and continues through to countless encyclopaedia and anthology entries about “Great Explorers”, as well as documentaries and feature films (Dyott’s book, for example, was made into a Hollywood film in 1958). Time and again, the myth outshines the man. The Amazon, into which Fawcett (and of course also the rescue expeditions) daringly ventured, is characterised as a hostile wilderness, a blank spot on the map, a black box where no one knows what to expect. This makes anything seem possible: dangerous monsters, hostile cannibals, and lost kingdoms that perpetuate the idea of a civilisation in which Indigenous communities that inhabit and cultivate the rainforest are seen only as threats, carriers, or whistleblowers. Fawcett himself becomes the ideal of the late Victorian male explorer who opens up unknown worlds as a conqueror. His earlier achievements and expeditions are honoured primarily as proof of his reliability, presenting him as a credible witness to entire hidden cities, lost civilisations with secret knowledge, and advanced technology. His rather spiritual interests in these topics are either glorified as eccentric exaggerations or convictions to be defended against the scientific establishment’s prevailing doctrine. This extends to his portrayal in fiction: when Fawcett meets Tintin (Hergé, The Broken Ear, 1935) or Indiana Jones (Rob MacGregor, Indiana Jones and the Seven Veils, 1991), he has found the hidden city and its inhabitants and stayed there, voluntarily or not.

The wider public became again aware of Fawcett’s story in 2005 with the publication of David Grann’s article in The New Yorker, “The Lost City of Z”. For his report, Grann travelled to Brazil in search of the expedition and also visited the Kalapalo. Using their stories as well as documents from the family estate and the Royal Geographical Society archives, Grann created a picture of Fawcett as a seeker in his reportage, which was expanded into a book of the same title in 2009. He was certainly not a sober scientist, nor was he a fantasist. Certainly not a prosaically scientist, but not a fantasist either, Fawcett’s obsession with the eponymous city was also an expression of the search for meaning in a modern age of emancipation between spirituality and electrification, which gradually heralded the end of the era of classic exploration (and explorers). Fawcett was convinced that this city of Z had to exist. He was determined to find it, at any cost. He really was determined to find it. Despite all the drama surrounding his expedition, it is perhaps precisely this failure that makes us feel particular connected, as it reveals the man behind the myth.

In his book (which was made into a film in 2016 starring Sienna Miller and Charlie Hunnam as Nina and Percy Fawcett), Grann also seeks to rehabilitate Fawcett’s idea of archaeological monuments are hidden in the Amazon rainforest. While there, the reporter also meets Michael Heckenberger, an anthropologist and archaeologist at the University of Florida, who takes Grann on an excursion and shows him what appears to be an unspectacular depression in the forest. However, it turns out to be part of a vast circular ditch system. One of many comparable along the upper reaches of the Rio Xingu, as Heckenberger explains. All these enclose settlements, each about two to three kilometres apart and onnected by roads and dams laid out at right angles. It is said that there were once more than twenty such villages and towns – with a population of two to five thousand, which could easily compete with European cities of the time. Around 1,500 years ago, a complex settlement system, Kuhikugu, was created here and existed until around 400 years ago.

Fawcett noted finds of decorated pottery shards, and he was impressed by the Indians’ ingenious fishing methods and their cultivation of floodplains for farming. But he interpreted these achievements as aftermath of an advanced civilisation that had once thrived there. Fawcett’s tragedy lies in the fact that he drew the wrong conclusions from the right observations, because he was missing the last piece of the puzzle: With images of the monumental ruins of the Maya and Incas in mind, he had expected to find colossal pyramids and temples. Not reckoning with the fact that the large settlements that once existed here had been built from wood and earth due to a lack of stone as building material, and which had eroded and rotted over time. He was deceived by the stories of conquistadors and adventurers from earlier centuries, who claimed to have seen stone pillars and arches in the jungle (and who in turn were probably deceived by bizarre weathered forms). Like his contemporaries, he accepted the small Indian tribes scattered throughout the forest as the original state rather than the result of contact with earlier European colonisers (who still reported large settlements).

Perhaps we should accept this sense of change as Fawcett’s legacy, as a plea to observe and trace it more closely. One passage in particular stayed with me as I reread Grann’s report. The reporter describes how he and a local guide drove past a spot on the Rio Manso where, 80 years earlier, Fawcett had become separated from his two companions in the thicket. However, instead of dense rainforest, a wide plain passes in front of the car window (“… the terrain looked like Nebraska …”). When asked where the forest was, Grann’s guide simply replies: “Gone.”