We often hear about the next “sensational” archaeological discovery in the news. In this case, however, that’s really not an exaggeration. When the discovery of a sandstone stele, apparently depicting an Iron Age warrior, was announced in 1996, each of its little details was a sensation in itself, especially in view of a nearby burial from the same period that had been discovered just two years earlier. At the same time, this is a wonderful example of how special discoveries in archaeology are not so much constituted by a single object, however spectacular it may be, but rather by the context in which such an object is found, which often could tell the more exciting story.

In this case the whole story begins with an important Celtic oppidum (a fortified settlement), a whole ritual landscape even, dating to the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods of the 5th century BCE, located at the Glauberg in Hesse, Germany, about 50 kilometres northeast of Frankfurt. The site was already known to archaeologists, but things became more exciting in 1988 when traces of a large burial mound were discovered just south of the oppidum. Thorough excavations between 1994 and 1997 revealed that the mound, originally measuring about 50 metres in diameter and probably six metres in height, contained two burials: A cremation and another inhumation within a larger wooden chamber.

Photo: S. Teschke, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

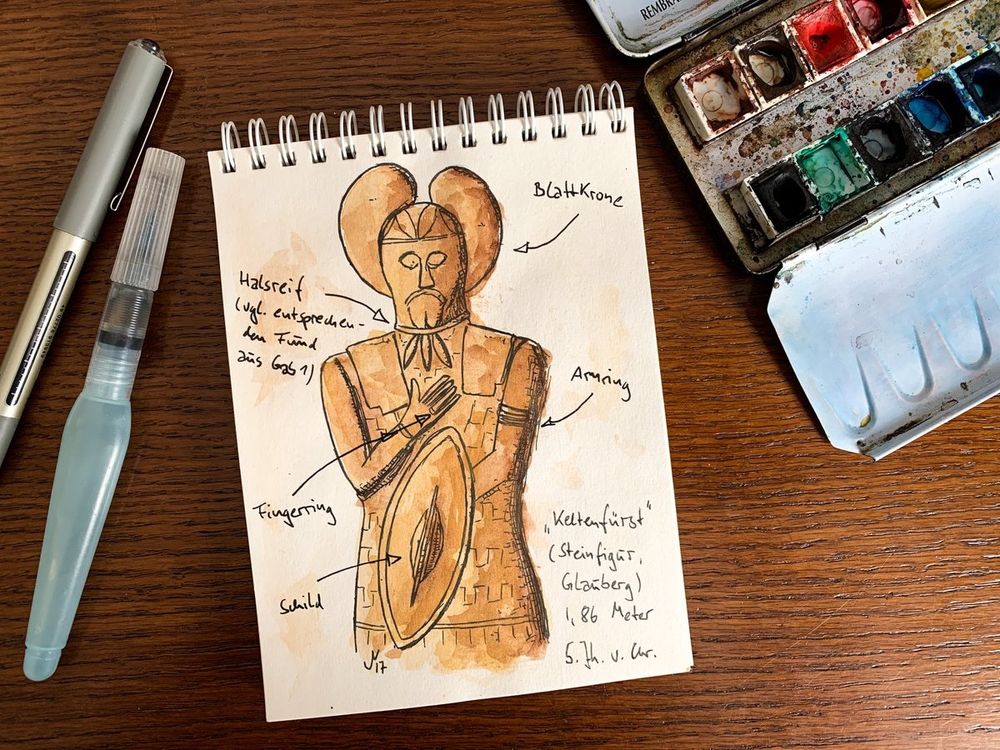

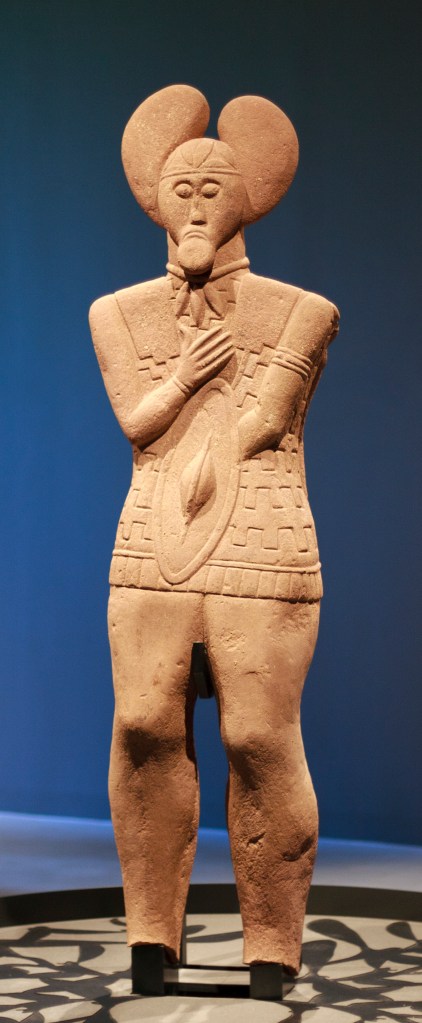

But then, just outside this mound (now referred to as “Hügel 1”) something really extraordinary came to light: An impressive sandstone statue, which (perhaps to the chagrin of social historians) has since become known as “Keltenfürst” (Celtic Prince). Impressive not only because of its (more than) life-sized proportions measuring about 1.86 metres in height (the feet are missing, unfortunately) and weighing some 230 kilograms, but also because of what it actually depicted: The figure, apparently a man, as it is wearing a fine moustache and, around its neck, a torc – a large metal ring typically associated with high-ranking individuals (in particular when made of gold). And this individual here clearly appears to pose as a “warrior” of some kind, presenting a shield right to the front of them and carrying a sword on their right hip.

However, what makes this stele so particularly fascinating is that all these small details depicted there have an actual, a real and tangible counterpart in the neighbouring burial mound! In the burial chamber there, iron rim and the boss of a shield were found, identical to the one carried by the warrior statue. And that typical La Tène sword which was also unearthed there alongside the remains of a scabbard, also closely resembles its stone counterpart.

One might argue that swords and shields are mere standard equipment in such graves and that corresponding finds therefore hardly should be surprising. Fair enough. But it doesn’t stop there! When it comes to the jewellery depicted, similarities are even more striking. The torc worn by the sandstone warrior, complete with its three striking pendants, as well as arm and finger rings all have exact parallels among the grave finds. The golden neck ring consists of two parts: a smooth neck section and a more elaborately decorated chest section featuring figurative and floral elements. As there are no signs of wear on the ring, it is questionable whether it was ever actually really worn (and if so, not very often). It may well have been made specifically as a burial object – which then makes the depiction of an identical ring on the stone stele all the more remarkable.

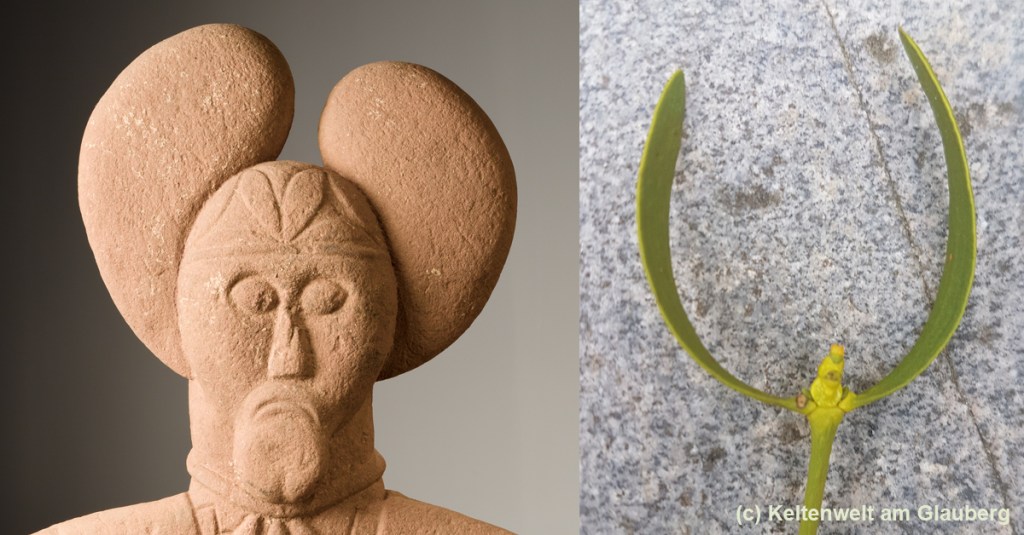

And then, well then there’s this guy’s iconic headgear: Two large, upward-curving … things that, admittedly, bear a suspicious resemblance to stylised Mickey Mouse ears. But this is, of course, no early Iron Age Disney cosplay. More likely it is a ceremonial “crown”, or rather cap, representing stylised mistletoe leaves, of which some fragmentary remains were also recovered from the burial in question … which really should not come as a surprise at this point.

Reconstructions, which of course must always remain interpretations, have imagined the original cap – of which, unfortunately, only supporting wires remain today – in rather different ways: From simple designs that inevitably evoke that Disney association, to a thoroughly practical, albeit somewhat eccentric, cap.

That mistletoe interpretation is, however, well-founded. The subtle difference in size of both “ears”, or rather leaves, already gives it away – since this is also characteristic for mistletoes. And in his Naturalis historia, Pliny the Elder described a unique relationship between Celtic druids and this plant. And although he wrote centuries later and from a Roman perspective, his remarks indeed seem to suggest that the mistletoe played a special ritual role – which is also reflected in its prominence among archaeological findings from the Celtic Iron Age.

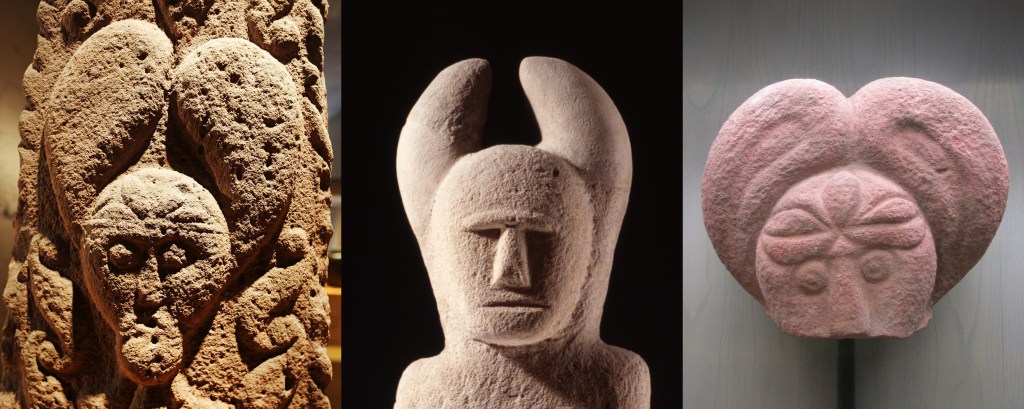

This symbolism, as shown by the Glauberg cap, is not an isolated case. Similar headdresses have been found on the Pfalzfeld Obelisk and the two-faced Holzgerlingen figure as well as a fragmentary sandstone head uncovered at Heidelberg, to just name a few. There are a couple more related depictions known with other figures, jugs, plates, coins etc. from Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, France, and England.

Photos: Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn, CC BY-SA 4.0 (left), P. Frankenstein & H. Zwietasch, Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart, CC BY-SA 4.0 (centre), AnRo0002, CC0 1.0 (right)

In case of these Glauberg finds, the parallels between grave furnishing and statue raises some fascinating questions: Was the sculpture a realistic portrait of the deceased? Or was the burial arranged to reflect some mythical ideal, represented by this figure? Was the Glauberg “warrior” a hero, leader, or ritual specialist? Or did he perhaps combine all three of these roles?

However, this story does not end with just one statue. Fragments of at least three other figures, which are very similar, were discovered in the surrounding area. They probably were placed in a rectangular arrangement around the burial mound, perhaps as stone guardians or forming a memorial ensemble. Glauberg, that much becomes clear, was not an isolated site, but the location of a carefully and deliberately planned ritual orchestration.