When Irving Finkel, esteemed Assyriologist and Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures at the British Museum, who’s always good for some really great public outreach on the fascinating ancient past), put up his interpretation of a stone plaquette from the early Neolithic site of Göbekli Tepe, Türkiye, on the Lex Fridman podcast last week, online discussion soon started buzzing with excitement. Did this small stone represent the very beginnings of writing, about 12,000 years ago? And did archaeologists really overlook such an important find all this time? (Spoiler: No, it doesn’t. And we didn’t.)

Photo: I. Wagner, DAI Göbekli Tepe Project

Finkel is a gifted narrator, and like many others, I am always happy to be swept away by his enthusiasm. All the more so, then, must I admit that some of the remarks he made on the podcast left me a bit irritated. What surprised me in particular was the subtle passive-aggressive attitude towards archaeologists that has become so noticeable in online discussions lately, to which even he does not seem entirely immune.

Screenshot via Lex Clips on YouTube

Finkel said, he stumbled upon the object which piqued his interest among a number of “photographs, which the archaeologists unwisely put online” and he seemed amused, noting (somewhat patronisingly) that apparently “so far no one said anything about it at all.” To then go on and offer his own interpretation of that stone object, suggesting that it was “a stamp to ratify, where the carvings of the signs on clay or some other sealing material would leave an impression” – and subsequently a form of writing.

Well, being one of “the archaeologists” in question, I first and foremost assure you that we did not put these photographs online unwisely, but indeed on purpose and as part of academic and public reporting on our research progress – like e.g. in an earlier post over at the Göbekli Tepe project’s research weblog “The Tepe Telegrams” back in 2016 (including a fairly accurate and thoughtful description of just that stone) or in our (award-winning, ahem) Antiquity paper from 2012.

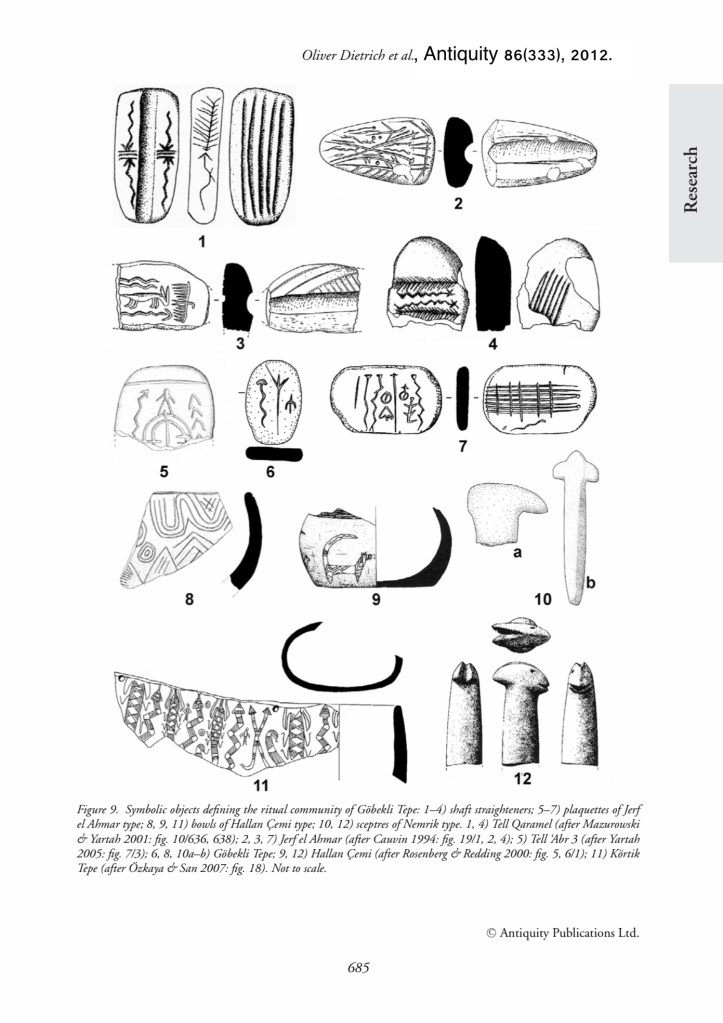

And as fascinating this one stone may seem – it does not come out of nowhere, nor is it a singular object. It belongs to a type of “plaquettes” (that particular type named after Jerf el Ahmar, another Neolithic site in northern Syria, where many more have been found) – the German name “Zeichentäfelchen” (small sign tablet) giving away the common perception that these stones seem to to have served no purpose other than bearing these incisions. Which fit well into the Pre-Pottery Neolithic iconography, as seen in a variety of similar depictions on other finds, such as stone vessels, shaft straighteners and architectural elements like the now famous T-pillars. An iconography apparently shared over a wider region, forming a common set of symbols within a large-scale exchange network.

Map: Th. Götzelt, DAI Göbekli Tepe Project (emphasis J.N.)

Interestingly, among these depictions there are some which indeed appear to be symbolic substitutes for more complex images, like the bucranium (ox head) in place of a full aurochs, or arrow-like zigzag lines representing snakes, and large birds reduced to a few characteristic lines. These depictions and their “abbreviations” seem to adhere to a certain convention, kind of a standardisation even, suggesting a communication system that uses these stone objects as media to store important information and knowledge. An idea, by the way, not really as new as the current discussion seems to imply. In their initial publication of that very object in 2007, Çiğdem Köksal-Schmidt and Klaus Schmidt already discussed its potential role in a Stone Age symbolic system, alongside that of other types of mobile art. Schmidt later elaborated further on this line of thought in a whole book edited together with Egyptologist Ludwig Morenz in 2014.

Illustration: J. Notroff

Even the question whether these Neolithic stone tablets could be considered precursurs of later Mesopotamian seal stamps has already been addressed and throughly discussed. Scholars like Sarah Kielt Costello, for example, who in a 2011 Cambridge Archaeological Journal paper was “Re-viewing the Antecedents of Writing” (and we’ll meet a familiar plaquette there, although Costello also concludes that these objects were probably used as mobile information devices rather than stamps). Or Kim Duistermaat, who offered “Some thoughts on the non-administrative origins of seals in Neolithic Syria” in an edited volume published in 2012.

Long rant cut short: Claiming that no one ever said anything about the amazing and complicated symbolic iconography of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Anatolia would only be true if we chose to ignore about 20 years of, admittedly not conclusive and ongoing, discussion. It’s great to see people are interested in the things we dig up and try to wrap our heads around in long library and study sessions – and frankly, we archaeologists are more than happy to talk and share our thoughts about this stuff (seriously, Irving, reach out next time!).

So, is it now writing or not? I’d still be hesitant, to be honest. These symbols are part of a communication system, I’m totally on board here. But in my humble opinion we’re not seeing phonetic values assigned to specific symbols representing spoken language here yet.